Model of soil freezing and thawing

In many practical applications, heat conduction is the dominant mode of energy transfer

in a ground material. Within certain assumptions (Kudryavtsev, 1978; Andersland and Anderson, 1978)

the soil temperature ![]() can be simulated by a 1-D heat equation with

phase change (Carslaw and Jaeger, 1959):

can be simulated by a 1-D heat equation with

phase change (Carslaw and Jaeger, 1959):

The quantities ![]()

![]() and

and![]()

![]() represents the volumetric heat capacity and thermal conductivity of

soil, respectively;

represents the volumetric heat capacity and thermal conductivity of

soil, respectively; ![]() is the volumetric latent heat of fusion of water, and

is the volumetric latent heat of fusion of water, and ![]() is the volumetric water content. The heat equation (1) is

supplemented by initial temperature distribution

is the volumetric water content. The heat equation (1) is

supplemented by initial temperature distribution ![]() , and boundary

conditions at the ground surface

, and boundary

conditions at the ground surface ![]() and at the depth

and at the depth ![]() . We use the Dirichlet

boundary conditions, i.e.

. We use the Dirichlet

boundary conditions, i.e. ![]() ,

, ![]() . Here,

. Here, ![]() is the

temperature at

is the

temperature at ![]() at time

at time ![]() ;

; ![]() and

and ![]() are observed temperatures at

the ground surface and at the depth

are observed temperatures at

the ground surface and at the depth ![]() , respectively.

, respectively.

One of the commonly used measures of liquid water in the freezing soil is the volumetric

unfrozen water content (Anderson and Morgenstern, 1973; Osterkamp and Romanovsky, 1997; Watanabe and Mizoguchi, 2002; Williams, 1967). There are

many approximations to ![]() in the fully saturated soil

(Galushkin, 1997; Lunardini, 1987). The most common approximations are associated with power

or exponential functions. Based on our positive experience in Romanovsky and Osterkamp (2000), we

parameterize

in the fully saturated soil

(Galushkin, 1997; Lunardini, 1987). The most common approximations are associated with power

or exponential functions. Based on our positive experience in Romanovsky and Osterkamp (2000), we

parameterize ![]() by a power function

by a power function

![]() for

for

![]() (Lovell, 1957). The constant

(Lovell, 1957). The constant ![]() is called the freezing point

depression. In thawed soils (

is called the freezing point

depression. In thawed soils (![]() ), the amount of water in the saturated soil is

equal to the soil porosity

), the amount of water in the saturated soil is

equal to the soil porosity ![]() . Therefore, we assume that

. Therefore, we assume that

where ![]() represents the liquid pore water fraction. For example, small values of

represents the liquid pore water fraction. For example, small values of ![]() describe the liquid water content in fine-grained soils, whereas large values of

describe the liquid water content in fine-grained soils, whereas large values of ![]() are

related to coarse-grained materials in which almost all water freezes at the temperature

are

related to coarse-grained materials in which almost all water freezes at the temperature ![]() .

.

We adopt the parametrization of thermal properties proposed by (de Vries, 1963; Sass et al., 1971)

with some modifications. We express thermal conductivity ![]() of the soil and its

volumetric heat capacity

of the soil and its

volumetric heat capacity ![]() as

as

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the effective volumetric heat capacities, respectively, and

are the effective volumetric heat capacities, respectively, and ![]() and

and ![]() are the effective thermal conductivities of soil for frozen

and thawed states, respectively. For most soils, seasonal deformation of the soil

skeleton is negligible, and hence temporal variations in the total soil porosity,

are the effective thermal conductivities of soil for frozen

and thawed states, respectively. For most soils, seasonal deformation of the soil

skeleton is negligible, and hence temporal variations in the total soil porosity, ![]() ,

for each horizon are insignificant. Therefore, the thawed and frozen thermal

conductivities for the fully saturated soil are obtained from

,

for each horizon are insignificant. Therefore, the thawed and frozen thermal

conductivities for the fully saturated soil are obtained from

where subscripts ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() mark heat capacity

mark heat capacity ![]() , thermal conductivity

, thermal conductivity ![]() for ice at

for ice at ![]() , liquid water at

, liquid water at ![]() and solid soil particles,

respectively. Combining formulas in (4), we derive that

and solid soil particles,

respectively. Combining formulas in (4), we derive that

Hence, the thermal properties ![]() and

and ![]() are expressed by only four variables such

as

are expressed by only four variables such

as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Evaporation from the ground surface and from within the upper organic layer can cause

partial saturation of upper soil horizons (Kane et al., 2001; Hinzman et al., 1991). Therefore, formulae

(4) need not hold in the presence of live vegetation and within organic soil

layers, and possibly not within organically enriched mineral soil (Romanovsky and Osterkamp, 1997).

Besides organic and organically enriched mineral soil layers, there are other horizons,

all of which can have distinctive physical properties, texture and mineral composition.

We assume that there are several horizons, namely: an organic layer, an organically

enriched mineral soil layer, and a series of mineral soil layers. We assume that physical

and thermal properties do not vary within each horizon, and hence ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

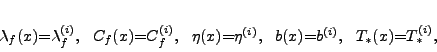

![]() can be assumed to be constants within each soil horizon:

can be assumed to be constants within each soil horizon:

where the index ![]() marks the index of the soil layer. Table 1 shows a typical

soil horizon geometry and the commonly occurring ranges for the porosity

marks the index of the soil layer. Table 1 shows a typical

soil horizon geometry and the commonly occurring ranges for the porosity ![]() , thermal

conductivity

, thermal

conductivity ![]() and the coefficients

and the coefficients ![]() ,

, ![]() parameterizing the unfrozen

water content.

parameterizing the unfrozen

water content.